|

Previously an '80s synthpop icon and now popularly considered an innovator and perhaps even instigator of electronic rock,

Gary Numan has seen a career resurgence after he took his music in a darker, harder, and -- according to him -- more genuine

direction with his 1994 album "Sacrifice." Over ten years have passed since, and he's released a quintet of darker

industrial-edged albums and has received respectful nods from modern music alumni ranging from Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson,

to The Bravery and The Foo Fighters.

Near the end of his Jagged Tour in August, Mr. Numan was kind enough to spend some time in San Francisco speaking with

us about different aspects of his music, including how having children can only make his music darker, his creative struggles

during the middle of his career and how some of his music is so close to his heart that he can't perform it live.

By Geoffrey Smith II

RSJ: It's been five years since you first toured the US. How's the response been from fans this time around?

GN: It's been really good, actually. Considering it's been such a long time since the last tour, you kind of expect to

start again; any sort of interest or momentum built up will be long gone. Lots of people are playing, and even people like

Bruce Springsteen are downsizing, so the fact that we've done as well as last time we toured here is encouraging. We need

to come back more often. We plan to come back in March or April of next year, and then again in September or October. Rather

than disappearing for years, coming back and trying to salvage it, we'll just keep coming back and trying to build it and

build it, which is something I've never done here.

RSJ: How does touring in Europe compare with touring in the US?

GN: I would put Britain separate from Europe -- not just because I'm English and a little weird about stuff like that.

(laughs) But it is a bit different; I'm much more successful in Britain than I am in the majority of Europe. There's a slightly

different vibe. The people that turn up, largely, are actually quite cool. You go down to Birmingham and it's an exciting

night. But there is an added level here [in the US]. You sing a chorus here, and it goes quiet during the chorus and people

start cheering in the gaps. You don't get that so much in England. You wait until the end of the song. It's a subtle difference,

but we all notice it.

And a really good American crowd is just brilliant -- it picks you up all the time; it makes you want to work harder.

It's great; I love it. Except for Philadelphia. (laughs) And Jacksonville. We did Jacksonville on the last tour. Shit. Worst

gig of my life that was -- 27 people [showed up] and all of them must have been at the wrong gig.

RSJ: Wow.

GN: It was rubbish. They had pool tables, and they were all lit up and people were [playing] on them, and they were just...over

there, and we were over here...doing our gig. And somebody got shot as we were coming out of the [venue], and some woman came

screaming down the street that her boyfriend had been shot in the head.

RSJ: And what happened in Philadelphia?

GN: Philadelphia wasn't that bad...Philadelphia's all right; I'm speaking a bit bad of it, but it was definitely the quietest

crowd, the least responsive crowd of this tour so far. But it was still excellent. You just get so used to [shows] being really

phenomenal and really exciting, and if one of them dips just a little below that -- although it's probably better than anything

you did in Europe -- you kind of notice it.

RSJ: Tell me about the live band for this tour.

GN: Well, most of the members have been around forever. Richard Beasley on drums has been with me for god knows how long.

Ade Orange on keyboards has been with me for even longer. I actually don't remember when most of these people joined -- I

think Richard was '93. David Brooks is on keyboards and bass now. And Chris McCormick on guitar; he's not been with us before.

The guitar player I normally use -- there were two, actually, were Steve Harris, who defected to a band called Archive, and

then Rob Holliday who's in a British band called Sulpher --

RSJ: -- who produced your last album, "Pure."

GN: Right. He's now a guitar player with The Prodigy. He was going to do this [tour], but he needed to miss two Prodigy

gigs to do it, and they wouldn't let him. So I rung up Chris McCormick to see if he was available, and luckily, he was.

RSJ: Do you ever miss Ade's giant, orange hair?

GN: (laughs) No, he does.

RSJ: Was it ever distracting onstage, like maybe you saw it out of the corner of your eye, this big orange mass --

GN: -- like Ronald McDonald! (laughs) No, he looks cool now, too. The best thing he could've done was getting rid of

it.

RSJ: Tell me about the group dynamic you guys have.

GN: We're with each other all the time, even when we're not on tour. It's a fantastically close-knit happy little group

of people; everyone gets [along], all the wives and girlfriends get on really, really well. There's hardly ever friction of

any kind, not even with all the stresses and strains of being on the road and away from your friends and family. I can't

imagine doing it any other way. Being onstage, for us, is just like walking around a house together.

RSJ: How do tours from the '80s compare to now -- do you miss more of the visual stage elements?

GN: It would be nice to be big enough to still do those great big shows, but they were unbelievably expensive. All of

that stuff [giant pyramids, light shows, etc] was custom built. The setup costs alone were astronomical. I was regularly

-- in the beginning of my career -- losing money on these shows with the understanding that we were making it up on the records

and could afford it.

But it's not like that now, with record sales. I probably won't make any money with this album. Not the original release,

anyways. We're going to do an extended mixes version of it and a DVD version, and with all those combined, I'll probably make

a little bit of money with it. It's really, really difficult with all of the downloads -- we've looked at these download sites

and know that there have been more illegal downloads of the album than we've actually sold.

The other side of it is, because I've been [touring] for such a long time now, and I'm that much more confident and I

enjoy being onstage, is that I've been able to learn. In the old days, with the great big shows, I was rubbish to look at.

I couldn't dance. I would just stand there trying to look enigmatic. And I just looked boring, really. I look at those old

videos and cringe. I was really wooden onstage, and the truth is that every single movement I thought about, "Maybe I

should lift my arm now." It was so unnatural. And now it's natural as breathing.

RSJ: I notice you tend to play immediately upon hitting the stage, without any sort of announcements.

GN: I don't talk to the audience either. I say thanks once, maybe twice if I'm really feeling good. Maybe it doesn't come

across the way I always thought it did. It just feels bullshit-free. We go on, do it, [and we're] gone. There's not a whole

lot of shite like, "Hello Cleveland, we love you!" (laughs)

RSJ: The last few albums have seemed a lot more personal than previous ones. Do you ever find it hard to perform certain

songs onstage?

GN: Yeah. There's a song called "Little Invitro" on the last album that I can't do. I've tried it twice now.

It's about when one of our babies died; it's not the easiest thing to do. And there's another called "One Perfect Lie,"

and it's about when my dog died. That was a really horrible thing. There's a few things like that, which as soon as you start,

the whole thing comes right back to you. And I guess because when you're onstage, you're in a kind of heightened emotional

state, it seems to hit much harder than when you're just at home and put [the record] on and listen to it.

RSJ: Tell us about the Telekon mini-tour coming up in December.

GN: Well, all the songs will be from the "Telekon" album or associated b-sides and singles of that era. Tonight,

we won't do many old songs, but the ones we do, we revamp so they're huge and sound like they belong with the new album. However,

when we do the Telekon tour we'll probably keep the songs a little closer to how they sound on the original album. I am aware

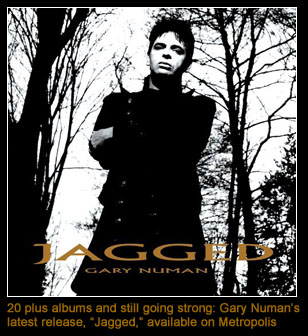

that there are fans that've been around for quite a long time and want to hear more of the old stuff. I must be up to twenty

albums now, and the majority of my catalogue never gets played, so the idea of doing these album [based] shows is really a

gesture to those people.

RSJ: Do you plan to dress differently for these particular shows?

GN: I'm not sure, actually. I don't want to recreate 1980, because I'm a different size for start. I don't want it to

become cheesy; I want a proper musical visit to that album. But I don't want to start reliving my youth -- red stripes or

that sort of shit again. I actually don't know what I'll do, and I don't know if what I wear now is appropriate for those

songs --

RSJ -- you're very intimidating now, compared to the "Telekon" era.

GN: (laughs) I'm too small to be intimidating. It might not work as well with these songs -- I was in a different mind

when I wrote [the album] and filled with teenage angst. And so it's going to be kind of weird going and doing the industrial

thing with that type of music. I haven't decided yet what to do, but I think it will just come natural.

RSJ: Aside from these Telekon shows, what else do you have planned?

GN: The next album we're hoping to get ready for September or October of 2007. Get the album out, tour more often, just

build it, really. It's getting a bit late in my life to be getting it right. It would be nice to do this properly, the way

I should have done in the beginning and just see if it makes any difference. I had a talk with the record company man today,

and he's not the most optimistic about the state of the music scene here in general -- industrial side in particular. It's

just fading.

RSJ: Since "Jagged" has been released, do you feel any differently about it?

GN: Yeah, it's too slow. Certainly the next album will be much more aggressive, faster. I think the structure of "Jagged,"

the verses are quite haunting, almost pretty, but are lacking really big anthemic choruses.

But it's the same with any album you make. You make it, and six months later you go back to it, and it's easier then to

notice what's wrong with it. I definitely think the next one will be better, more exciting than this one and a lot more exciting

to play live. And the next one should be absolutely huge -- the overall sound of it is going to be absolutely massive.

RSJ: I remember you had some issues working with your previous label in the US; how's working with Metropolis been?

GN: Metropolis is great. Spitfire...shit! (laughs) Why was I even there? I'm not precious about record companies at all,

but they were the worst. By miles.

RSJ: You say that you don't listen to much music in your free time; do you think this helps in maintaining creative vision?

GN: It might, I guess. That's not why I don't listen to music, but it could. I'm not particularly tainted by what the

current fashion is or what's in the chart. I don't really know who's successful or who isn't, because I don't follow it. I

can't remember the last time I listened to radio. When I'm in my car, that's where I do all my thinking -- but because I now

have kids, I can't think anyways. (laughs)

RSJ: You said before that "Magic" is probably the only optimistic track that you've created. But now that you

have a couple children and a wife, and your career is seeing a resurgence, do you think that's going to change?

GN: No, I really don't. Especially with having the children. "Jagged"'s the first album I released since I've

had children, and [the music] has not softened at all. The thing about having children is, even though they're lovely and

so on, I just worry about them now. And looking after them, and the things that can happen, and the horrible people lurking

around. There's just a whole new world of shit that opens up when you've got kids. (laughs)

I couldn't write happy songs, anyways. Some people can just write happy little tunes, and I can't. If anything, it's just

going to get darker. Certainly more aggressive. Much more. It's still a little bit too...nice. Too pretty.

RSJ: Do you have albums that you are more or less proud of?

GN: I have massive favorites. The whole period I'm not particularly happy with is from about '83 to '92. [The albums]

were all right, but they became less and less Numan, if that makes any sense. I've always been really bothered by the fact

that I'm not a particularly good player; I can't write songs very well, play keyboards very well, I'm not a particularly good

singer. So, my answer to that was to progressively take me out of it -- to add more and more backing singers, to get in a

proper guitar player, and so on. Which I thought was the right thing to do, but now I don't.

What I actually did was take out all the things that made a Numan album a Numan album, because while I may not be the

best guitar player, I do have a certain way of playing it, and it gives me the sound and style that I have. [It was] my wife

Gemma, who eventually made me realize that whatever it is you've got, whether you think it's worthwhile or not, other people

do and like it.

RSJ: What was your philosophy after this?

GN: Just go back to working the way you used to, where you used to [experiment]. And so I did that, and created an album

called "Sacrifice," and it was immediately a much heavier and darker album than what I'd previously done throughout

the '80s. When I first started, I was very focused and knew exactly what I wanted. And as my career struggled, I started

to panic a bit; I started to write songs for the wrong reasons. People say you'll get accused of selling out as soon as you

sell a lot of records. But that's not selling out; that's just being lucky. Selling out, for me, came later. When you start

writing songs not because you really like the song you've written but because you think it might get you on the radio, that's

selling out. And I did that. Way too long.

RSJ: Yeah?

GN: I'm really ashamed of myself; I honestly am. I did an album in 1992 called "Machine and Soul," which was

really a pile of cack, fucking useless. I was really chubby then. I had run out of ideas. I didn't know what I wanted to sound

like, I looked like shit, was in massive money problems with people trying to repossess my house, and my girlfriend was off

fucking some cameraman. Rubbish all around, really. I did this really rubbish album, and then that was about the time I met

Gemma.

I had a really massive rethink about everything, why I was in the business and did I want to stay in it, why I was writing

songs, and why I wrote songs the way I did. Then I decided to give up on the whole attempt to salvage the career and just

went back to doing what I liked as a hobby -- what it used to be when I first started. I didn't have a contract at the time,

[but I] just made an album for the hell of it. And that was "Sacrifice."

Doing the "Sacrifice" album, I enjoyed making it, and when you realize you haven't enjoyed making music the

previous five or six [albums], it's only when a big change comes along that you realize just how far wrong you've been in

the past. I just didn't see how far away [I'd gotten] from everything that I thought was the right way to be about music.

Luckily, it was just in the nick of time that I got it back. And it was just as that happened, that people like Trent

Reznor started talking about me, and all of a sudden there's a lot of interest again. If that had happened a year or two before,

it would have been a disaster. Trent Reznor would have said something nice about me, and some people would have gone out and

listened to "Machine and Soul" and thought it was an absolute pile of shit -- which it was -- and would have never

looked at me again. So, that whole wave of interest would have been wasted. But it came at just the right time, so, it's just

luck, really. It's been a weird career.

Got something to say about this feature? E-mail us.

|